My dog sits perfectly during the training sessions, but looks at me with a blank stare when I ask her to sit when we’re in the park. Why is it that dogs can’t figure out that ‘sit’ in my house is the same as ‘sit’ in the park? Learning is more than accumulating a series of experiences, of memories, a list of different sequences of muscle activation. When we’re teaching our dog to ‘sit’, there is more going on in his mind than just the word ‘sit’ and the behavior ‘put my butt on the ground’. Learning is about classifying information and defining predictable patterns. The ability to generalize, meaning, to apply what we learned from limited experience to new situations depends on the architecture of the system, the grand organizer of it all: the brain.

My dog sits perfectly during the training sessions, but looks at me with a blank stare when I ask her to sit when we’re in the park. Why is it that dogs can’t figure out that ‘sit’ in my house is the same as ‘sit’ in the park? Learning is more than accumulating a series of experiences, of memories, a list of different sequences of muscle activation. When we’re teaching our dog to ‘sit’, there is more going on in his mind than just the word ‘sit’ and the behavior ‘put my butt on the ground’. Learning is about classifying information and defining predictable patterns. The ability to generalize, meaning, to apply what we learned from limited experience to new situations depends on the architecture of the system, the grand organizer of it all: the brain.

Let’s take a simple task that most of us do on a regular basis: driving. When we’re driving on the highway, there are countless numbers of sensory inputs, some visual, others muscular, olfactory, auditory, etc. The sky may be cloudy with different shades of gray and blue, birds may be flying around, there are houses and buildings along the road, electric lines on the poles, our back muscles may be a little tense, there is a slight smell of gas in the air… On and on, our sensory system is bombarded by myriads of information. Thank goodness, we don’t have to deal with all of it! Our brain sorts out what is relevant for us. In this situation, the road, the signs, the other cars, our speed, how much gas we have in the tank, is the only needed knowledge to safely get to our destination.

When we’re teaching our dog to sit what becomes relevant to us is the dog’s behavior, the cue ‘sit’, our timing and how we deliver the reward. One of the biggest difficulties we can have when working with another species is that, as our brain categorizes information in a particular situation, we naturally assume that the animal is living the same experience. In the same situation, the dog may be focused on our tone of voice, our posture, the type or rewards we’re using, the smell that comes off our clothes, the sound of the water boiling on the stove top, etc. It’s easy to tell a child to focus on the shapes of the letters as we teach him to write, but without verbal information to frame and focus the training setting, we can’t tell our dog to focus on the sounds that come out of our mouth, not on our hand twitch or head nod. Just our sensory world alone is so different that we can’t even imagine what it would be like to smell as many different smells as we see different colors and shapes. When we also add how many more sounds dogs can hear, it’s mindboggling to think of how distracting the world would be without the brain filtering and making sense out of such magnitudes of information.

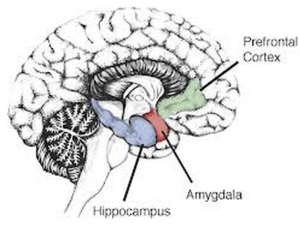

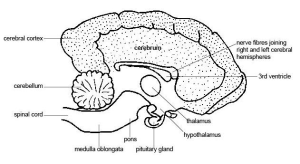

Human Section of the brain

The neocortex, also referred to as the association cortex, more developed in humans than in other species, is specialized in learning the regularities in the environment (Norman & O’Reilly, 2003). Pulling all the information together, the neocortex identifies similarities between events and makes it possible to generalize, to build representaions, in other words to adapt to a new situation similarly to one that we have previously encountered. So once we’ve learned how to drive one car, we can quickly adjust and drive different cars, small trucks, go carts or any moving object with four wheels, a steering wheel and two pedals that we classify as a vehicle.

Another neural structure involved in learning is the hippocampus. This structure, very similar across all mammals, functions almost to the opposite of the neocortex by memorizing specific events. The hippocampus seems to play an important role in the acquisition of new memories but unlike the neocortex, that will over time, develop similar representations for similar stimuli, the hippocampus will quickly form distinct representations of the different stimuli.

So what does this all mean? Since our neocortex is far more developed than the neocortex of our companion dogs, we are much more apt at generalizing than they are. It’s second nature to us to identify similarities in different situations, so much so, that it leads us to draw conclusions when we are missing parts of the information. We’re quick to put reasons behind other people’s actions when they unconsciously remind us of similar situations. In the same way, without question, we identify as feelings of guilt the look on our dog’s face when we find a puddle in the living room because it looks like what another person would express in a similar situation. We’re also subject to optical or cognitive illusions as we’re automatically making assumptions about the world.

For the dog, details may have more significance than they do for us, so what they learn in our kitchen doesn’t easily translate to being the same thing when in the park. This doesn’t mean that dogs won’t generalize at all, In fact, when it comes to strong emotional experiences, such as fear, only one scary event has the potential to leave lasting consequences in the dog’s behavior. But in the end, not only will dogs and people focus on different categories of information, we’ll also memorize the situation in slightly different ways.

To help our dogs learn that ‘sit’ means ‘put your butt on the ground’ in all situations, it therefore becomes necessary to repeat the training in as many different settings as possible. As we make changes, what we’re also doing is making anything other than the word ‘sit’ irrelevant. Since the word becomes the only constant, the dog gradually learns to pay more attention to it and gives less focus to non-verbal or situational information. Sitting on a chair, on the floor, standing up, raising an arm, both arms, changing our tone of voice, our posture, all of those differences that are merely irrelevant details for us, make a world of difference for our canines. We’ll also have to make sure to repeat the process in living room, in the back yard or in the park. As the dog starts responding in all these different situations, we’ll gradually start introducing distractions. During the entire process, anytime we introduce a new variable, we’ll have to drop our criteria, which will allow the dog to learn the process again in different setting.

Unlike humans who have developed unequaled abilities to draw generalities and constants in our environment, dogs can be considered as master discriminators. They’re great at picking out the smallest details in our behavior or in the environment. This ability is also what sometimes leads us believe that they can read our minds or predict when we’re coming home from work. The smallest details that we simply don’t pay attention to, are relevant sources of information for the dog. Taking these differences into consideration allows us to adapt our training protocols, making sure that we set our dogs up for success and give them the exposure and repetitions they need to learn with fluency.

Jennifer Cattet Ph.D.

Related articles

Interesting!

While a scary event can leave lasting consequences, part of the learning mechanism is thought to be somewhat different (survival), also happens with people, and many dogs experience years of abuse but then recover quickly. I mention this only due to the number of people who assume a scared dog must have been hit or abused to cause this behavior, when simple lack of experience and learning is more often the case.

Beyond, I agree with all your points, but will add that these characteristics may widely vary between dogs (and people). For instance, after teaching “sit” in the house, nearly all dogs will transfer this behavior to the patio and most to the dog run. However, many will only partially follow this at the dog park with some not at all. As you noted, we should not assume but instead test the dog’s behavior in different settings.

Great post! I never stopped to think about why a dog would not listen in one place, but understand the command at home.

Hi Dr Cattet,

Interresting article, thank you.

I am very interested by generalization in dogs. We know that dogs are poor at generalization but they can be very very good in some situations. You wrote :

« This doesn’t mean that dogs won’t generalize at all, In fact, when it comes to strong emotional experiences, such as fear, only one scary event has the potential to leave lasting consequences in the dog’s behavior. »

So they can rapidly generalize about things that we would prefer they dont. If they can rapidly generalize in some situations, would it be possible to optimize the situations so they generalize more?

To your knowledge, is there research about generalization in dogs?

Is there information about rules of thumb about generalization in dogs (I frequently read about having to train in 5 to 8 different environments to have a good generalization).

It seems there is no information about good generalization procedures.

I hope I expressed myself correctly: English is not my mother tongue.

Thank you very much

Louis Cimon

Louis, your english is very good and you made yourself very clear. English is not my first language either so I appreciate how much effort it can be to write in a foreign language.

You nailed it, dogs may learn from a strong emotional event in just one episode, when we would prefer they don’t, and may take dozens of repetitions for behaviors we are trying to teach them.

Anytime I write a blog I look for research on the subject and incorporate it in the article. Unfortunately, this is one area that desperately needs more attention and all I found is already in the blog. If you come across any study on this, please share it with us.

Thanks,

Jennifer