While we understand that good behavior should be rewarded if we want the dog to repeat it, there are different opinions about how and how much we should reward our pooches. We might consider that a “good boy!” is a great way to communicate to the dog that he’s done something right, but is it really? Did we affect his behavior as much as we think we did? Does a pat on the head, an “Atta boy!” or a morsel of cheese all hold the same value to the dog? Of course not, that would be like saying that we would work just as hard for a pat on the back from our boss, for a “Well done!” or for a paycheck. Although we might appreciate the praise and attention, they will never compare to our paycheck! As Bob Bailey says: “it has to be worth the animal’s effort!” So how do we know when we’re using the appropriate reward and when we can do away without using treats?

While we understand that good behavior should be rewarded if we want the dog to repeat it, there are different opinions about how and how much we should reward our pooches. We might consider that a “good boy!” is a great way to communicate to the dog that he’s done something right, but is it really? Did we affect his behavior as much as we think we did? Does a pat on the head, an “Atta boy!” or a morsel of cheese all hold the same value to the dog? Of course not, that would be like saying that we would work just as hard for a pat on the back from our boss, for a “Well done!” or for a paycheck. Although we might appreciate the praise and attention, they will never compare to our paycheck! As Bob Bailey says: “it has to be worth the animal’s effort!” So how do we know when we’re using the appropriate reward and when we can do away without using treats?

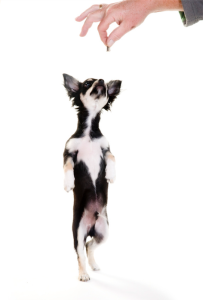

Positive reinforcement is the addition of a stimulus to increase a behavior. The “Law of effect” (Thorndike, 1927) states that when the consequence of a behavior leads to the animal’s satisfaction, the behavior is reinforced and likely to be repeated. This well known principle is at the core of animal training where we purposely manipulate the time and delivery of our reward in order to condition the animal to respond in a specific way to a particular cue. When the dog offers the behavior we’re looking for, we reinforce it with something of value to him/her. We can provide our dog with attention, food, praise, play, affection, toys, etc. Anything that the dog enjoys will act as a reinforcer. When opting for one reward or another however, it’s important to consider the potential value of the reward at any given moment. A piece of kibble may be a great reward in our kitchen, but when out in the park, playing with another dog will likely have more worth.

At the top of the list of rewards: food. As a primary reinforcer, in other words, as having innate biological value for the dog, food is generally a strong motivator for behavior. After all, no dog alive can do without eating. “Sit”, click – treat, repeat! Food is easy to use and to control. As a bonus, food has been shown to enhance the dog’s social behavior towards humans (Feuerbacher & al., 2014). When we use food, dogs show less avoidance behaviors and more attraction to people, especially to the person delivering the food. So more than just a training aid, food facilitates the bond that can develop between dogs and humans.

It’s possible that since we value praise and touch between ourselves, we also expect such demonstrations to have value to the dog. Despite a rise in the use of treats in dog training, most pet guardians still resist giving treats and when they do, they‘re often too stingy. Much like a pat on the back, we expect a stroke of our dog’s head to be enough to demonstrate our affection and approval. In fact, petting is also a primary reinforcer, and studies have shown that petting a dog has definite positive effect on our canine friends. The dogs’ heart rate and blood pressure decrease while endorphins, prolactin, oxytocin and dopamine increase (Odendaal & Meintjes, 2003). Such physiological responses clearly reveal the bonding, pleasurable and calming value of our affectionate touches. Stroking can therefore be used as a reward and is often the main means of reinforcing a behavior in Army dogs.

It’s possible that since we value praise and touch between ourselves, we also expect such demonstrations to have value to the dog. Despite a rise in the use of treats in dog training, most pet guardians still resist giving treats and when they do, they‘re often too stingy. Much like a pat on the back, we expect a stroke of our dog’s head to be enough to demonstrate our affection and approval. In fact, petting is also a primary reinforcer, and studies have shown that petting a dog has definite positive effect on our canine friends. The dogs’ heart rate and blood pressure decrease while endorphins, prolactin, oxytocin and dopamine increase (Odendaal & Meintjes, 2003). Such physiological responses clearly reveal the bonding, pleasurable and calming value of our affectionate touches. Stroking can therefore be used as a reward and is often the main means of reinforcing a behavior in Army dogs.

What about praise? We’re very used to giving a “Good girl!” or “Good boy!” as a way to express our satisfaction and reward our pet. If we think about it though, it’s a very human way of interacting with another being. Since our dogs don’t use words themselves and show no particular pleasure at the vocalizations of other dogs, what value does praise have for our canines? A couple of recent studies may hold the answers to this question: does praise really work?

In the first experiment, 15 dogs were trained to “sit and stay” and “come”. In a first stage, a “baseline training” the trainer stood a meter away, facing the dog then squatted on the floor. As soon as the dog gave her eye contact, she stood and came back to the dog. Once the dog was 100% successful at this task, the experimental training started.

In this second stage, the dogs were asked to “sit” and “stay”, then the trainer moved at a distance of 2, 3 or 4 m, faced the dog and gave the “come” cue. The cue was given in a very neutral and unemotional tone of voice. When the dogs responded correctly they were given one of three types of reward: food, stroking or praise (Fukuzawa & al., 2013).

Interestingly, there were no statistical differences between the 3 reward groups. All dogs learned pretty much at the same rate. This might suggest that no matter the reinforcer, it takes a certain number of repetitions for a dog to learn a task. This confirms previous studies that also found no significant difference in the number of training sessions needed to teach a behavior whether we use a clicker and treats or treats alone. The clicker however did seem to increase the resistance to extinction (Smith & Davis, 2008). Dogs may simply need a certain number or repetitions no matter the method. In this experiment, during baseline training however, the dogs learned much faster with food than with either stroking or praise. So in the early stages of training, using food made a big difference. When the value of the reward is higher, the animal learns faster and associates the behavior with a positive emotion, a satisfaction that increases the motivation to repeat the behavior. They will also respond faster, meaning they will get in position faster after hearing the cue when food is involved.

Interestingly, there were no statistical differences between the 3 reward groups. All dogs learned pretty much at the same rate. This might suggest that no matter the reinforcer, it takes a certain number of repetitions for a dog to learn a task. This confirms previous studies that also found no significant difference in the number of training sessions needed to teach a behavior whether we use a clicker and treats or treats alone. The clicker however did seem to increase the resistance to extinction (Smith & Davis, 2008). Dogs may simply need a certain number or repetitions no matter the method. In this experiment, during baseline training however, the dogs learned much faster with food than with either stroking or praise. So in the early stages of training, using food made a big difference. When the value of the reward is higher, the animal learns faster and associates the behavior with a positive emotion, a satisfaction that increases the motivation to repeat the behavior. They will also respond faster, meaning they will get in position faster after hearing the cue when food is involved.

A second study explored further the effects between verbal praise and petting by testing shelter dogs and owned dogs. The dogs were evaluated on their desire to interact with a person depending on whether they talked to them or touched them. When stroking, the person petted the dog with one hand on the side closest to them so the dog would never feel trapped. The person scratched or petted whatever body part was closest to him/her. When using vocal praise, the person talked to the dog in a happy and high pitch tone of voice and said words like: “you’re such a good doggie! What a sweet doggie you are!” The experimenters measured the dogs’ choice to be with one or the other person depending on the type of interaction under different conditions (Feuerbacher & Wynne, 2014).

Across the board, the dogs spend much more time with a person when petting was involved rather than praise alone. Even when a stranger was petting the dog and the owner was in the room providing vocal praise, the dogs walked away from the owner to enjoy the physical contact. More surprising was the fact that the dogs would not spend any more time with a person talking to them than simply ignoring them!

We’re a vocal species so it’s quite natural to interact in that way with our dog. We seem to talk to our dogs in the same way that we talk to infants. But whether or not this type of interaction has much value to canines is definitely in question. The best way to make sure that praise can play a role in operant conditioning is to pair it with a primary reinforcer like food, and even petting. Through deliberate conditioning, praise can add to our arsenal of rewards and effectively contribute to training. But just like any other type of reward, it all depends on the dog’s internal state and motivation of the moment, doesn’t it?

Jennifer Cattet Ph.D.

Feuerbacher EN1, Wynne CD. (2014) Most domestic dogs (Canis lupus familiaris) prefer food to petting: population, context, and schedule effects in concurrent choice. J Exp Anal Behav. 101(3):385-405

Fukuzawa, M., Hayashi, N. (2013) Comparison of 3 different reinforcements of learning in dogs (canis familiaris). Journal of Vet. Behav. 8, 221-224.

Odendaal, J.S.J., Meintjes, R.A., (2003) Neurophysiological correlates of affiliative behavior between humans and dogs. Vet. J. 165, 295-301

Smith, S.M., Davis, E.S., (2008). Clicker increases resistance to extinction but does not decrease training time of a simple operant task in domestic dogs (canis familiaris). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 110, 318-329.

Thorndike, I.L. (1927). A fundamental theorem in modifiability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 13, 15-18.

The reason that ‘praise’ works is because it is a secondary or conditioned reinforcer.

If the human pairs praise with everything that they give the dog that the dog wants, then praise becomes a pretty string reinforcer on its own.

You can then use praise in situations where a primary reinforcer cannot be used.

Of course, if you think of it, praise is also only a conditioned reinforcer for humans. I presume that it works best in social species where social approval is of prime importance. Praise is an efficient way of signalling social approval.

Praise also is a very powerful reinforcement for those who use various types of collars to administer corrections, because it signals being safe from that correction.

Praise is all I use . For a job well done . Praise must be real from the heart for it to work . I do not use food as bait or a reward . It is not necessary. I believe that if one feels that bait is required for the dog to perform then something is missing in the leader dog relationship. This should be assessed. For myself it is all about communication between leader and dog and dog and leader.

Well I also think that praise is better approach in order to have positive result. The more you praise the more dogs will do better. I also personally praise my dog and believe me it results well. Moreover thank you so much for sharing this information. Keep posting and keep growing.